- Home

- Amy Sonnie

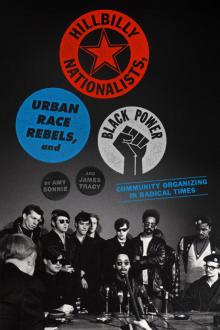

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power Page 9

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power Read online

Page 9

The Peace and Freedom Party (PFP), founded to capture the votes of the country’s growing progressive electorate, nominated Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver to take on Republican Richard Nixon, Democrat Hubert Humphrey and southern Independent George Wallace for the presidency. Both PFP and the Panthers saw their alliance as mutually beneficial. PFP publicized the Panther program, while the Panthers helped broaden PFP’s voter base among communities of color and radical whites.58 Some radicals saw the ballot box as a waste of time, but Cleaver and PFP believed putting radical candidates into the electoral arena would “illuminate the inadequacy of establishment politics” and incubate a unified front against racism and imperialism by specifically focusing on public education and outreach.59

Peggy Terry and Doug Youngblood were already working to sway southern white voters away from segregationist George Wallace, authoring articles and leveraging what contacts JOIN had. To those who knew her, Terry seemed a natural choice for running mate, but the decision was far from unanimous. At the PFP convention, Cleaver asked for the Yippies’ Jerry Rubin or SDS leader Carl Davidson. When neither was willing, members put forward a range of names including Terry’s. Cleaver wasn’t satisfied. He called for a meeting with his top aides in private. JOIN’s Mike Laly barged in with Panther founder Bobby Seale, exclaiming, “What could be better than running a black ex-con and a working-class white woman for president and vice president?” Cleaver’s aides ejected the two, but Terry’s advocates persisted from the convention floor. Eventually a compromise was struck—Peace and Freedom Party members could nominate their own vice president state by state. Of the thirteen states where the new “fourth party” qualified for a ballot slot, Terry appeared on the ticket in California, Minnesota, Iowa, Kentucky and Illinois.

Cleaver wasn’t the only one who had misgivings about the pairing. Movement women were confounded that Terry had partnered with a convicted rapist who described raping white women as an “insurrectionary act” in his book Soul on Ice. Terry wasn’t much of a Cleaver fan, nor did she ever expect to win office. She entered the race so she could go toe-to-toe with George Wallace for the allegiance of poor white communities.

After a failed bid for governor in 1958, Wallace’s popularity skyrocketed when he embraced pro-segregation policies in the early Sixties.60 During his first term as governor Wallace honed his racist rhetoric and argued that federal civil rights legislation violated “states’ rights.” He deliberately fortified his national reputation during a 1963 “stand in” against school integration when he personally blocked the entrance of two Black students to the University of Alabama.61 Moving further and further away from his affiliation with the Democrats, by the time Wallace ran for president he had joined the American Independent Party and garnered the backing of the KKK and White Citizens’ Councils across the South. As his campaign picked up steam, it illustrated that racism was alive and well far beyond the southern states. In New York, twenty thousand supporters filled Madison Square Garden. In Boston, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and San Diego he drew crowds in the tens of thousands.

Peggy Terry focused her campaign on confronting Wallace, while exposing the hypocrisies of the other candidates as well. On October 1, Terry invited Wallace to a national televised debate. The next day she followed with an official announcement about her plans to take on Wallace’s deception of the people. “His ‘little man’ appeal has won over many white workers who are tired of their unions’ cooperation with big corporations. But Wallace is not the answer to their problems. He is just another kind of boss,” she wrote.62

Wallace never accepted Terry’s invitation, but she kicked off her campaign anyway with former JOIN member Mike James as her campaign manager. It began at an Iowa drive-through restaurant with a gathering of welfare recipients, SDS activists and high school students who were organizing around a student bill of rights. The owner, disturbed at the large crowd, called the police. Terry and three other organizers were detained as they exchanged power fists and V-signs, for victory, with the high schoolers. The youth taunted the police until the activists were released. The chaos spilled over to the local high school where the principal was challenged for attempting to confiscate radical literature from students. At a supporter’s home, Terry sat down with the students to answer questions and offer advice on everything from protest tactics to control of the curriculum.

Terry’s forces were not so warmly received in all cities. In Louisville, Kentucky, just a few hours from her hometown of Paducah, students at a local high school heckled Terry’s caravan and challenged her positions on nearly everything. Weren’t they just draft dodgers? Why were they trying to start a riot? They asked Terry to leave their school, but not before a local reporter documented the incident and students’ clear disinterest in Terry’s message.63 Terry persisted, making several other stops in Kentucky before heading to California. Cleaver, at just thirty-four years old, wasn’t old enough to be president, so both California and Utah listed only his running mate on the ballot. As a neighborhood organizer with limited experience on the national scene, Peggy Terry was largely unknown among progressives in California or elsewhere. Her son Doug Youngblood worked hard on this aspect of her campaign, writing and speaking to progressives about the need to abandon middle-class tunnel vision. If PFP or the New Left overall hoped to outrank Wallace, let alone the “demopublicans,” the movement needed to make itself more relevant to working-class people just as JOIN had argued all along.64

Terry, too, pled her case in a lengthy Los Angeles Times article, but ultimately the Cleaver–Terry ticket won just 0.4 percent (or just under 28,000) of the state’s votes. Wallace garnered half a million. His 6.8 percent of the vote was four times higher than the American Independent Party’s membership in the state.65 Nationwide Wallace received ten million votes and carried the total vote in five southern states. Nixon, of course, won the national election with 43 percent of the vote, only slightly more than Humphrey. Cleaver–Terry garnered less than one percent in every state. Though actually winning was never the goal, Terry’s goal of inspiring poor whites outside of Uptown proved more difficult than she anticipated. In the end, Terry doubted whether working-class whites or even the PFP’s liberal white membership understood her message.

Peggy Terry never considered the campaign a failure though. Like the long talks she had around her kitchen table in Uptown, the Peace and Freedom campaign was an opportunity for yet another protracted conversation, worthwhile if just a few people started to think differently. While an injury—sustained when a police officer kicked her in the back at a protest—required invasive surgery and took Terry out of the movement for several years after, she never ceased in her role as an educator and lifelong proponent of radical causes. Terry did what she did out of love for people. “I love people who aren’t organized,” she said. “But it’s up to me to find a way—to find the words, to make them understand that there’s more to life than today’s pleasures.” Laughing that she might sound a bit like a preacher “fired up to save souls from hell,” she add, “I want to save them from capitalism.”

In the end, JOIN Community Union saved more than a few. What set them apart from their contemporaries was the realization that it was futile to ask someone to challenge an empire if they didn’t feel powerful enough to challenge their landlord, insist on their right to health care, refuse the draft or stand up to a corrupt police department. Projects like the welfare committee, housing strikes and Goodfellows illustrated their successes. After a series of joint actions with welfare organizations in other states, the Dovies and Welfare Recipients Demand Action helped to build the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO). At its peak in the late Sixties, the NWRO boasted twenty thousand members from hundreds of regional welfare groups.66

JOIN’s welfare committee also laid the foundation for women’s leadership in Uptown as local women forged their own vision of women’s liberation dealing with race, class and gender oppression simultaneously. At a time when many midd

le-class feminists alienated poor women and women of color, Chicago’s early feminist movement was deeply influenced by poor women’s leadership, in large part because of JOIN and Welfare Recipients Demand Action. During their time at JOIN several women leaders also helped found the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, one of the oldest feminist organizations in the country.

Perhaps JOIN’s biggest legacy is the number of organizers that, through their shared experience, became lifelong radicals. The inspiration they found and the outrage they experienced empowered a core of white radicals who “never left the Left,” as Marilyn Katz put it. According to Jean Tepperman, whether students or dislocated southerners, “Nobody, well almost nobody, truly left JOIN.” Their effort to build a sustained, progressive working-class movement in Chicago inspired new projects that eventually succeeded in changing the face of Chicago politics and the visibility of poor whites in the movement. Just months after JOIN closed its doors, the Goodfellows founded the Young Patriots Organization and formed an unprecedented alliance with the Black Panther Party. Within a year, JOIN’s Mike James, Diane Fager and Bob Lawson also founded Rising Up Angry, an organization that spent nearly a decade organizing working-class whites across Chicago and forging partnerships with radical working-class whites in other states.

In 1983, Katz and others who had come through JOIN helped get Chicago’s first Black mayor, Harold Washington, elected. Most saw Washington’s victory as the culmination of two decades of work, beginning in the Sixties and continuing into the Seventies through the Young Patriots and Rising Up Angry. Their projects proved that barriers to progressive, multiracial alliances were not immutable, and that poor and working-class whites had a leading role to play.

CHAPTER 2

The Fire Next Time:

The Short Life of the Young Patriots and

the Original Rainbow Coalition

We’ve got to face the fact that some people say you fight fire best with fire, but we say you put fire out best with water. We say you don’t fight racism with racism. We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity.

—Fred Hampton, Chicago Black Panther Party, 1969

April 4, 1969, marked the one-year anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the urban uprisings that set hundreds of cities ablaze. In the year since, millions of U.S. residents changed their calls for equality to demands for a second American Revolution. At the helm of that movement was the Black Panther Party, widely regarded as the vanguard of the radical Left by 1969. While the Panthers were best known for asserting their right to “police the police” by carrying guns in self-defense, the group’s national influence grew because of their exemplary work serving breakfast to hungry kids, their cogent internationalist politics and their commitment to building alliances. In Chicago, Panthers Bob Lee and Fred Hampton spearheaded one such alliance, knowing the move would garner more controversy than clout.

The Rainbow Coalition initiated by the Panthers united poor whites, Blacks and Latinos in a “vanguard of the dispossessed.” In addition to the Chicago Panthers, its members hailed from the Young Lords, a group of mainland Puerto Ricans who turned their decade-old street gang into a radical political organization, and the Young Patriots Organization, poor “dislocated hillbillies” descended from JOIN Community Union’s anti-police brutality committee.1 The Young Patriots took pride in their southern roots and newfound independence from the middle-class Left. From afar these urban hillbillies looked like any other white street gang, young men in their twenties and late teens dressed in white T-shirts, black pants, and sleeveless jean vests or leather jackets with their group’s signature hand painted on the back. Each wore perfectly greased hair, unless covered by a cowboy hat, and a clean shave. Up close there were telltale signs setting them apart from other neighborhood guys: buttons that read “Free Huey” and “Resurrect John Brown,” another showing two fists breaking a set of chains. To hear them speak was even more telling; these cats were about something different. As one Patriot put it, “Before we are proud of who we are, let us be proud of who we are supposed to be.”2 For the Young Patriots, that meant “revolutionary solidarity” with oppressed people around the world, starting with the Black Panthers and Young Lords in Chicago.

In Spring 1969, members of the Rainbow Coalition made their first joint appearance at a press conference on the anniversary of King’s murder. Crowded around a long folding table, dressed in black leather jackets and dark sunglasses, they projected an image of ultimate revolutionary cool—albeit a male-dominated one. Black Panther Nathaniel Junior sat at the microphone to urge the city’s poor to stop fighting each other and tearing up their own neighborhoods. Street rebellions grew from an understandable grief and rage, they argued, but only invited police retaliation. It was time to decrease petty turf wars and quell pointless violence. It was time for poor people to claim their rightful place leading movements for revolutionary change in Chicago and beyond.

The Patriots may have formed with or without the direct influence of the Chicago Panthers, but there is no doubt that the Black Panther Party lent primary inspiration, theoretical framework and a programmatic model to the Uptown organization. The Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California, in October 1966 by seasoned activists and community college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton to address two of Oakland’s biggest problems: police brutality and the city’s dangerous neglect of poor neighborhoods.3 One of their first actions highlighted the city’s culpability in a child’s death at a dangerous intersection where residents had long demanded a stop sign. Newton and Seale, with a shotgun in hand in case anyone tried to interfere, went to the intersection and installed stop signs themselves. As young black intellectuals who studied the writings of Marx, Lenin, Mao, W.E.B. DuBois, Malcolm X and Frantz Fanon among others, Newton and Seale also showed just as much dedication to revolutionary theory as they did to planning actions. Their study of theory, particularly around questions of socialism, nationalism and self-determination, inspired the Panthers’ famous ten-point manifesto poetically outlining demands for community control, housing, health care, meaningful employment and an end to racist judicial practices. Embodying their call for self-determination it began, “We Want Freedom. We Want Power to Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community.”

That freedom required, first and foremost, an end to the constant police harassment in Black neighborhoods. During their first few months the Black Panthers started community patrols to protect residents from police. They came armed with legal doctrine and firearms, letting furious officers know that citizen observation of police was protected under the law. In response, city and state officials decided to change the law, making it illegal for citizens to openly carry loaded firearms. Shortly thereafter, in May 1967, the Panthers catapulted into the national spotlight when they showed up to the Sacramento State House brandishing rifles. They certainly got the attention of lawmakers, including a young actor-turned-Governor Ronald Reagan, but the Panthers’ real target was the media. Frenzied reporters snapped photos of the shocking spectacle as thirty Black men and women, outfitted in sleek leather jackets, berets and shiny rifles marched across the capitol lawn. For the mainstream public, the event focused more attention on the group’s militancy than its message, but for radicals and even a few left-leaning liberals the Panthers’ stand was a lightning rod, a dramatic and well-planned theater of the oppressed.

The Panthers’ stong self-defense position garnered attention, but this wasn’t what ultimately earned them the support of grandmothers in Uptown, actors Jane Fonda and Marlon Brando, famous musicians and more than five thousand Panther rank-and-filers. While the Panthers’ history is filled with internal strife and its leaders were far from perfect, the media’s sensational reporting obscured the group’s biggest contribution: In city after city Black Panthers spent most of their daily energy on community service, a strategy they called “Survival Pending Revolution.” In practical terms, they provided the basic services people desperately needed

, including a popular free breakfast program, sickle cell anemia testing, legal defense clinics, literacy classes and schools that taught children cultural pride and Black history for the first time.4

More commonly referred to as the “Serve the People” approach, the Panthers’ service model reached thousands of families each day. This approach changed the terrain for dozens of radical community groups. Inspired by the Panthers, many stopped waging long, resource-intensive campaigns to win paltry concessions from social welfare bureaucrats. Instead radicals increasingly created community-run solutions. Though this certainly wasn’t the first time U.S. radicals had created autonomous social services, the Panthers’ service-plus-organizing approach offered a necessary alternative for community organizers who had more than a few reasons to question the point of reforming a broken system. Soon Latino, Asian, Native American and white radicals were putting forth their own revolutionary platforms. By 1967 the Panthers model inspired dozens of other organizations from the Chinese I Wor Kuen to the Young Patriots and the Puerto Rican Young Lords Organization.

In Chicago, the Young Lords Organization started out as a street gang similar to the neighborhood social networks the Young Patriots grew from. Based in the city’s large Puerto Rican community not far from Uptown, the Young Lords evolved into a political party under the leadership of Jose “Cha-Cha” Jiménez who developed a close relationship with movement groups including the West Coast Panthers. In 1967 the group launched its own service programs including drug education, food and toy giveaways and “Soul Dances” in collaboration with another local gang, the Blackstone Rangers, who had been a security force for Martin Luther King Jr. during the Open Housing Marches the prior year. Fred Hampton reached out to both groups about joining the Rainbow Coalition. The Lords agreed. The Rangers declined. While they supported the unity message, the Rangers ultimately drew the line at Left politicking and the groups’ identification with Third World Marxism. The Lords embraced it, expanding to other cities like New York and continuing to grapple with their own precarious circumstance as internationals whose homeland had been seized as a territory of the U.S. at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.5

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power